The following measures should be included in any programs aiming to provide newborn care at the household level. Additionally, program managers should engage health care providers—including community health workers and traditional birth assistants—to implement the following measures:

3.3.1 During the Antenatal Period

Photo credits: IRC/Kelli Ryan

- Identify pregnant women early through outreach and community informants, or through an antenatal care register at the local health facility.

- Conduct an initial visit with pregnant women in their homes. Identify women in preterm labor and refer to nearest health facility for care.

- At that visit, promote the use of formal health facilities for antenatal care, birth and postnatal care.

Provide information to families and community leaders about the closest facility, including mobile clinics, location, hours of operation and options for transport to the facility, including emergency transport. In crisis settings where access to facilities is not safe or is not possible with additional resources, ENCabbreviation services can be provided through ongoing home visits (Section 5.3). While WHOabbreviation recommends eight antenatal visits commencing early in pregnancy (first trimester),[1] a minimum of four is recommended in humanitarian settings.

Key activities in this period center around birth preparedness and complication readiness, including developing a birth plan with the woman and family that includes emergency transport, security and monetary considerations.

- To ensure a clean delivery, families should be provided with a clean delivery kit (Box 3.5) with instructions on how to use it in the event that healthcare facilities are inaccessible or unavailable.

- Counsel women on nutrition during pregnancy, reduced workload, risk of the particular infectious disease outbreaks that might increase burden of disease (if known).

- Provide health education on prematurity, preterm labor and care for small babies.

To prevent/manage infections:

- In malaria endemic areas, distribute ITNabbreviation to pregnant women for use during pregnancy and after birth, and educate women and families how to use the ITNs (e.g., after birth, the newborn sleeps with the mother under the ITNabbreviation).

- Provide TTabbreviation vaccination as required and screening and treatment for STIsabbreviation. Where this is not possible, counsel women to visit the local health center as soon as possible in order to access HIVabbreviation, STIabbreviation and malaria interventions, as well as vaccinations.

Box 3.5: Inter-agency Reproductive Health Kits for Crisis Situations

The IARHabbreviation kits have been designed to facilitate the provision of priority reproductive health services to displaced populations without medical facilities or where medical facilities are disrupted during a crisis. They contain essential drugs, supplies and equipment to be used for a limited period of time and a specific number of people. Some of the medicines and medical devices contained in the kits may not be appropriate for all settings. This is inevitable as these are standardized emergency kits, designed for worldwide use, that are pre-packed and kept ready for immediate dispatch. In addition, not all settings may need all kits, depending on the availability of supplies in a setting prior to a crisis and the capacity of the health facilities. The kits are not intended as resupply kits and, if used as such, may result in the accumulation of items and medicines that are not needed.

Once basic reproductive health services have been established, the reproductive health coordinator should assess reproductive health needs and attempt to order based on consumption, to ensure that the reproductive health programme can be sustained. You can order supplies through regular channels [the national procurement system, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or other agencies] or through the UNFPAabbreviation Procurement Services Branch. For more information, please see the Manual on Inter-Agency Emergency Reproductive Health Kits for Use in Humanitarian Settings. Distributions can be done at registration sites or via community health workers where there is a network established.

At a minimum, kits should include

- 1 sheet of clean plastic for the women to deliver on (noting she should assume birth position of choice)

- a bar of soap

- a pair of gloves

- 1 new razor blade to cut the umbilical cord

- 3 pieces of string to tie the cord

- 2 pieces of cotton cloth (1 to dry and the other to cover the baby)

- 1 tube of 7.1% chlorhexidine digluconate antiseptic gel for clean cord care

Source: Inter-Agency Emergency Reproductive Health Kits for Use in Humanitarian Settings. Manual, 2019.

Source: IAWG. Inter-Agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Humanitarian Settings, 2018.

The importance of safe and respectful birth practices should also be introduced during pregnancy visits. One of the most critical interventions to prevent maternal and newborn death is the provision of respectful and quality care by skilled birth attendants in a health facility that is equipped with drugs and medical supplies needed to manage complications.

- Encourage birth in a health facility, but counsel families that if a birth happens to/is being planned to take place at home, they should arrange for a SBAabbreviation to assist with the home birth and/or should go to the health facility as soon after birth as possible for an examination of both mother and baby.

- Emphasize that mother and baby should not be separated, particularly immediately after birth.

- Discuss early and exclusive breastfeeding, cleanliness and safe newborn care.

3.3.2 Intrapartum and essential newborn care

Photo credits: Jhpiego

No birth is without risk and therefore all should be supported by a skilled birth attendant with access to referral care if complications arise.

- If labor (including premature) begins at home, support transfer to a health facility.

- During the birth, implement clean and respectful birth practices (Box 3.6 and Figure 3.2)

- Provide thermal care by immediately, thoroughly drying the baby and placing the baby on mother’s chest until the first breastfeeding, including colostrum (initiated usually within the first hour of birth where possible).

- For all newborns who are breathing at birth and do not require resuscitation, do not bulb suction the mouth and nose, and do not clamp the cord for at least one minute after birth.[2] For further details on cord clamping, see Box 3.7

- For babies who don’t start spontaneous breathing within 60 seconds clear the airway and immediately start tactile stimulation by rubbing the back and thorough drying.info See Box 3.8 and Figure 3.3 for further guidance.

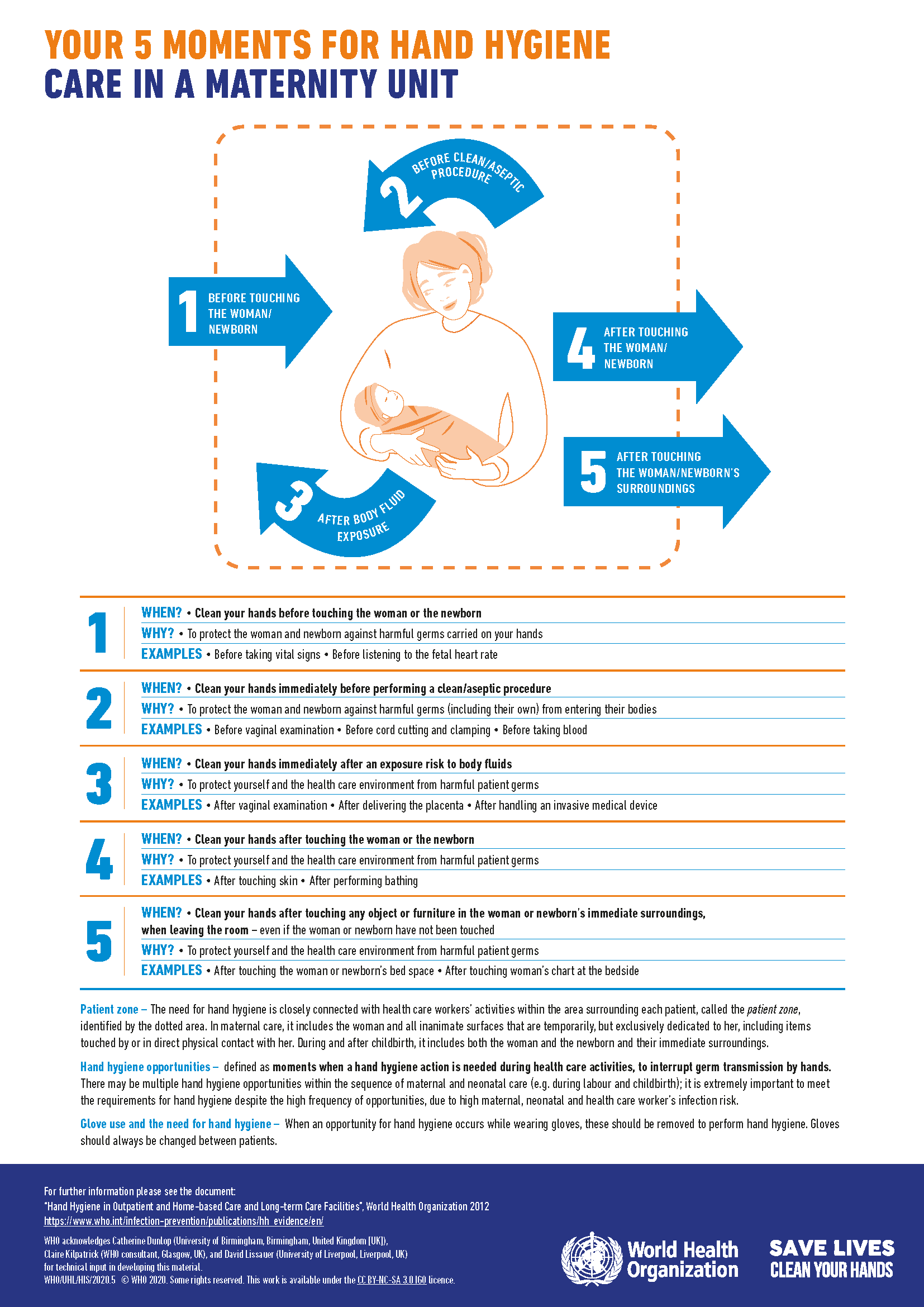

Box 3.6: Basic Preventive Measures to Reduce the Risk of Early Neonatal Infections

- Employ clean birth practices at birth

- Wash hands before and throughout birth

- Use sterilized gloves and supplies, including a clean surface, clean cord and tying instruments, sterile cutting instruments and a clean cutting surface.

- Ensure that the mother and family wash hands before handling the baby

- Emphasize hygienic cord care (see Box 3.9)

- Administer antibiotics to women with prolonged rupture of membrane

- Treat any maternal infections during pregnancy and labor

- Encourage early initiation of exclusive breastfeeding

Box 3.7: Optimal timing of cord clamping for the prevention of iron deficiency anaemia in infants

At the time of birth, an infant is still attached to the mother via the umbilical cord, which is part of the placenta. The infant is usually separated from the placenta by clamping the umbilical cord. Early cord clamping is generally carried out in the first 60 seconds after birth, whereas later cord clamping is carried out between 1-3 minutes after the birth or when cord pulsation has ceased. Delaying cord clamping allows blood flow between the placenta and neonate to continue, which may improve iron status in the infant for up to six months after birth. This may be particularly relevant for infants living in low-resource settings with reduced access to iron-rich foods. Delayed umbilical cord clamping (not earlier than 1 min after birth) is recommended for improved maternal and infant health and nutrition outcomes.

- In newly born term or preterm babies who do not require positive-pressure ventilation, the cord should not be clamped earlier than 1 min after birth.

- When newly born term or preterm babies require positive-pressure ventilation, the cord should be clamped and cut to allow effective ventilation to be performed.

- Newly born babies who do not breathe spontaneously after thorough drying should be stimulated by rubbing the back 2–3 times before clamping the cord and initiating positive-pressure ventilation.

- For basic newborn resuscitation, if there is experience in providing effective positive-pressure ventilation without cutting the umbilical cord, ventilation can be initiated before cutting the cord.

Source: Guideline: Delayed umbilical cord clamping for improved maternal and infant health and nutrition outcomes. WHO, 2014

Box 3.8: Helping Newborns Who Don’t Spontaneously Breathe

Up to 10% of newborns do not spontaneously breathe within the first “golden minute” after birth and require some type of assistance.

Most of these babies can be helped by opening the airway, rubbing the back and thorough drying.

However, some babies will require positive-pressure ventilation with the use of a self-inflating bag and mask. Ventilation should be stopped once the baby starts breathing or crying. Skilled birth attendants who are trained to recognize a non-breathing baby and immediately begin resuscitation can save newborn lives.

Note that without regular practice, health providers’ bag and mask ventilation skills quickly deteriorate. The establishment of “practice corners” with practice mannequins to support intermittent practice can help providers maintain their skills.

For further information, please refer to the Helping Babies Breathe resources. To refresh neonatal resuscitation training also see Module 9C in WHO’sabbreviation effective perinatal care training package.

3.3.3 Postnatal care

Photo credits: UNICEF/NYHQ2010-0266/Noorani

During the immediate postnatal period (within the first hour of birth)

- Ensure that the mother and newborn are not separated; continue thermal care by placing the baby, skin-to-skin, on the mother’s chest, and covering with a blanket and hat, for at least 60 minutes and until initiation of exclusive breastfeeding (usually within one hour) (Box 3.2).

- Assess breastfeeding and provide support where needed.

- Delay bathing the newborn for at least 24 hours to prevent heat loss and hypothermia.

- Monitor for danger signs (Box 3.3 and Box 3.4) and if danger signs are present, refer mother and baby to the nearest hospital for advanced care. Timely referral is critical to reduce mortality and morbidity. Where referral is not possible, please see Table 3.1 for further guidance.

- Continue clean practices such as handwashing for those handling the newborn to prevent infections (Figure 3.2).

- Provide clean dry cord care. In settings where the application of harmful substances on cords is prevalent, apply 4% CHXabbreviation (7.1% digluconate gel or liquid) to the cord (Box 3.9), in line with national guidelines.

- Educate women and families to look for danger signs (Box 3.3), and to seek care promptly when they are detected.

- Identify, support and if necessary refer newborns who need additional care

Box 3.9: CHX for Clean Cord Care at Home

As of 2022, daily application of 4% CHXabbreviation (7.1% chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution or gel, delivering 4% CHXabbreviation) to the umbilical cord stump in the first week after birth is recommended only in settings where harmful traditional substances (e.g. animal dung, dust, clay, mud) are commonly used on the umbilical cord (this is a context-specific recommendation.)

This recommendation is based on moderate-certainty evidence about the effects on neonatal mortality of applying 4% CHXabbreviation in the first week after birth in newborns with non-hygienic (harmful) cord care. In newborns with non-hygienic cord care, CHXabbreviation reduced mortality. In newborns without non-hygienic cord care, CHXabbreviation generally did not reduce mortality, although this may vary in settings with high rates of home births, high mortality, or high prevalence of facility-acquired infections.

WHO therefore recommends the application of 4% CHXabbreviation to the umbilical cord stump in the first week after birth only in settings where harmful traditional substances are commonly used on the umbilical cord. Application frequency varies, but evidence generally recommends daily administration from birth for seven days. In all other contexts, WHOabbreviation recommends clean, dry umbilical cord care for newborns.

Note that previous guidelines on CHXabbreviation recommended daily application to the umbilical cord stump during the first week of life for newborns born at home in settings with high neonatal mortality (30 or more neonatal deaths per 1000 live births). Clean, dry cord care was otherwise recommended for newborns born in health facilities and at home in low neonatal mortality settings. A number of countries have made adaptations to this standard and thus national policies should be followed as appropriate.

In 2019, the CHXabbreviation released [an alert regarding serious eye injury as a result of CHXabbreviation misadministration] (https://www.who.int/news/item/28-08-2020-chlorhexidine-7-1-digluconate-(chx)-aqueous-solution-or-gel-(10ml)-reports-of-serious-eye-injury-due-to-errors-in-administration), with reports of CHXabbreviation being mistakenly applied to the eye as eye drops or ointment. Managers and health workers should take steps to ensure clear and unique labeling of CHXabbreviation products, and to provide parents and other caregivers with detailed, culturally appropriate written materials and counseling on CHXabbreviation use.

Source: WHO recommendations on maternal and newborn care for a positive postnatal experience. WHO. 2022.

In case of Intrapartum Complications

- Transfer newborns with any evidence of complications, including breathing difficulties, for more advanced care as soon as logistically feasible.

- If CHWs or other cadres are trained to assist in home deliveries, they should have knowledge of the referral system and where advanced care is available nearest to the household before the birth, in case complications arise (see Section 5.2. Developing a Referral System).

For pre-term and/or LBWabbreviation babies

- Refer all babies born before 37 weeks gestation and/or all LBWabbreviation newborns (< 2500g/5.5 lb) to more advanced care (ideally, in a formal hospital setting; see below).

- Place all babies weighing less than 2500g/5.5 lb in STSabbreviation position with their mother or a surrogate and take them immediately to a health facility for follow up.

During the first week after birth (second hour following birth up to seven days)

For home births, ensure that a skilled health personnel or a trained community health workers is contacted to:

- Conduct postnatal care checks (i) as soon as possible within the first 24 hours, (ii) between 48–72 hours, (iii) between day 7-14 (iv) during week 6 after birth. Most maternal and neonatal deaths occur in the first three days after birth, in particular on the day of birth, with another increase in mortality during the second week after birth. It is therefore important that visits take place during these key windows to provide continuity of quality and respectful care. Home visits from trained health workers during the first week after birth are recommended for babies and women that are healthy and do not require additional care. Where home visits are not feasible or not preferred, outpatient postnatal care contacts are recommended.

- Weigh the newborn baby using a newborn weighing scale or a foot length card that has been calibrated to the local setting and record birth weight appropriately.

- Provide eye care by giving the baby a single dose of tetracycline hydrochloride 1% eye ointment in each eye for prevention of conjunctivitis.

- Provide the newborn with 1 mg of vitamin K intramuscularly (IM) and provide immediate vaccination according to national vaccination protocol. Commonly used vaccines for newborns immediately after birth are hepatitis B, Polio and BCGabbreviation for tuberculosis. Encourage hepatitis B vaccine in areas of high Hepatitis B endemicity.[3]

- Continue health promotion activities including promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, thermal care for the baby, hand washing for people touching the baby and hygienic cord and skin care.

- Continue to examine the baby for danger signs of serious illnesses, and continue to encourage the family to look for these danger signs (Box 3.3 and Box 3.4) and promote appropriate care seeking behaviour

- If danger signs are detected, facilitate access for the mother and baby to the closest health facility or hospital.

- Encourage HIVabbreviation-positive mothers to access HIVabbreviation testing and other care for their newborns.

- Inform women and families of the importance of an immunization visit for the newborn at 6 weeks.

For pre-term and/or LBWabbreviation babies

- Follow-up on all preterm and LBWabbreviation (<2500gs) babies after birth at home or discharge from the health facility through extra postnatal visits, preferably at home. These should occur on within the firs 24 hours, (ii) between 48-72 hours, (iii) between day 7-14..

- Ensure immediate referral to facility-based care for newborns showing any danger signs (Box 3.3) as well as signs of jaundice (Box 3.10).

Box 3.10: Identifying and Managing Jaundice

Jaundice is very common in newborns, estimated to be present in 60% of term babies and 80% of preterm babies. Although jaundice is not harmful in most cases, jaundice in premature and/or LBWabbreviation babies, or babies with other risk factors such as infection, can cause permanent brain damage and requires immediate and early attention. Signs of jaundice include yellow skin and eyes, and sometimes yellow palms and soles. All newborns should be monitored for jaundice and, when present, preterm babies, babies where jaundice appears on the first day of life, and babies of any age with yellow palms and soles should be referred immediately. Jaundice should be confirmed by bilirubin measurement and managed with phototherapy or exchange transfusion. Further guidance on the identification and management of jaundice in newborns can be found in this neonatology training module developed by WHOabbreviation EURO, JSI and USAID.

For babies exhibiting danger signs

Where referral or hospitalization is not possible, recent guidelines from WHOabbreviation[4] provide recommendations for antibiotic regimens provided by trained health care providers. Note that critical illness should always be treated in hospital and not outpatient facilities. If families refuse hospitalization or referral is not possible, the following recommendations (Table 3.1) should be considered by a trained health provider to provide an outpatient treatment of infection. Treatment regimens should be informed by disease surveillance systems when feasible and appropriate, to ensure treatment approaches consider local antimicrobial resistance trends.

| For infants with isolated fast breathing |

There are two recommendations for children with fast breathing as the only sign of illness whose families do not accept or cannot access referral, one for infants 0–6 days and one for infants 7–59 days of age.

|

|---|---|

| For infants with clinical severe infection |

Young infants (0–59 days) identified with clinical severe infection whose families do not accept or cannot access hospital care should be managed in outpatient settings by an appropriately trained health worker with one of the two following regimens:

|

| For infants with signs of critical illness |

Young infants 0–59 days old who have any sign of critical illness (at presentation or developed during treatment of clinical severe infection) should be hospitalized after pre-referral treatment with antibiotics. |

Source: WHO. Managing Possible Serious Bacterial Infection in Young Infants when Referral is Not Feasible. WHO, 2015.