Photo credits: Save the Children

The findings from the situation analysis should be used to inform the development of a unified strategy and response plan to deliver newborn health services. The strategy and response plan should include a summary of the key findings of the situational analysis, and services and programs to be developed and implemented in response. The SRHabbreviation coordinator should be engaged to designate partner leads and collaborators for types of services and geographic zones of delivery. These may include UNabbreviation agencies, government authorities, local and international NGOs, community-based organizations and the private sector. Where relevant, use the findings from the situation analysis to identify and partner with agencies not participating in humanitarian coordination mechanisms, particularly local and development organizations. Once finalized and approved by the SRHabbreviation working group, the strategy document will serve as an internal guide for the working group partners, as well as a tool for external advocacy.

4.3.1 Prioritizing newborn interventions

Based on the situation analysis and available local capacity and resources:

- Plan for the implementation of newborn health interventions, ensuring they are respectful and uphold quality of care of mothers and newborns during the acute response phase.

- Prioritize interventions outlined in the 2014 Lancet Every Newborn Series that showed substantial evidence in reducing neonatal mortality:

- Essential newborn care comprising thermal care, infection prevention, feeding support, monitoring for danger signs and postnatal care (Section 3.2)

- Neonatal resuscitation (see Figure 3.3)

- Kangaroo mother care for pre-term and small babies (see Box 3.2)

- Infection management for sick babies (see Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4, Section 3.5, and Section 3.6)

It is recommended that during the initial phase of a humanitarian response, the above essential interventions are prioritized for implementation, and that other interventions to complete the newborn package can be added in later phases based on the local context (for more details, please see Chapter 3).

In addition, the establishment of referral systems, including assessing the quality of the receiving facility,info for sick and/or small babies is essential to save newborn lives (See Section 5.2 for more information on developing a referral system.)

4.3.2 Update and distribute clinical guidelines and protocols

- Use findings from the situation analysis (Section 4.2) and newborn interventions prioritized to inform the selection and dissemination of key materials, including clinical guidelines and protocols. See the Resources section for a list of relevant knowledge and training materials.

- Ensure staff are equipped with a birth readiness check-list and newborn supply kits (Section 5.4) to support health facility readiness and birth preparedness.info

4.3.3 Develop and collate needs based staff training materials

Using the results of the staff assessment (Section 4.2.3), staff training materials should be developed or adapted, implemented and evaluated.

- Develop/adapt training content for your context based on the competencies expected for each type of provider (CHWs, nurses/mid-level staff, physicians) at each level of care (household, primary care facilities, hospitals) and the identified gaps in those competencies.

- Incorporate approved national and/or community-level MNHabbreviation key messages, referral system protocols and other foundational information into training materials, as appropriate. (Box 4.5)

Box 4.5: Planning and delivering coordinated health services: working with local providers and systems

Employ local health providers

If the situation allows, identify and train local health care providers. Avoid recruiting providers from outside the region. Local providers have the advantage of being familiar with the culture and language of the affected community, increasing the likelihood that MNHabbreviation services will be delivered effectively, efficiently and successfully.

Coordinate with government efforts

Work with the host country government to design and deliver training programs. Ministry of Health staff will know what curricula and other training materials are available in country, and can often assign trainers to deliver the training content as well as managers to support the training and supervision of trainees.

In crisis settings, training courses must be practical. Most situations will require the abridging of extensive information and education into brief trainings that health staff can complete within the restrictions of their work schedules and of the crisis situation. Types of training may include on-the-job sessions, practical or theoretical lessons in a classroom-type setting, structured training courses addressing a specific task or need, and refresher courses for experienced staff.

- Where possible, integrate MNHabbreviation into relevant humanitarian health trainings in the crisis setting. Examples of MNHabbreviation topics include safe motherhood, maternal health, infant feeding in emergencies, PMTCTabbreviation, IPCabbreviation and WASHabbreviation, IMCIabbreviation and ICCMabbreviation, respectful maternity care. Integration of these topics requires a high level of coordination with other organizations. However, this approach is recommended because it maximizes available training resources, including training personnel, funding and the time health professionals have available to participate in training courses.

- Review and evaluate trainees to ensure that new knowledge and skills are being applied in practice in household and clinical settings. Although challenging to implement and sustain within crisis settings, supervision and evaluation of provider practices are essential to the delivery of high-quality MNHabbreviation services.

- Engage supervisors from the local health system early on and invite their input to develop a plan for conducting timely follow-up visits with trainees. Assessments may include visits to observe, coach and solve problems with trainees, as well as to gather data and identify gaps in performance to strengthen providers’ skills on the job.

- Where possible, identify peer-practice coordinators to facilitate ongoing practice, which promotes retention of learning and changes in provider behaviour.

- Where site visits are not possible, consider remote supportive supervision, for instance through the creation of mobile chat groups (e.g., WhatsApp), text messages, online meetings to provide virtual technical assistance and facilitate peer learning

- Where possible, provide transport and other material support for local supervisors to ensure their active engagement in the supervisory process over time. When logistical challenges arise, such as impassable roads or security alerts that prevent local visits, on-site supervision may be suspended but must resume as soon as feasible.

Many countries might have developed their own MNCH assessment tools that could be used. For other sample tools see WHO harmonized health facility assessment resources.

4.3.4 Procure and distribute essential medicines and supplies

Building on the information gathered as part of the RHAabbreviation (Section 4.1.1) and the resource assessment process (Section 4.2.3), clearly define the process for distributing medicines, medical commodities and supplies to support newborn care. To effectively distribute kits, up-to-date, accurate information about the supply chain is essential. Document the distribution process and monitor needs regularly. See Section 5.4 for further information on procuring newborn supplies.

4.3.5 Ensure quality improvement and respectful care

Poor quality of care contributes to maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity. Estimates suggest that if quality was improved for selected antenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal interventions to benefit pregnant women and newborns seeking care, there could be a 28% decrease in neonatal deaths, and 22% fewer stillbirths compared to a scenario without any change or improvement in quality of care.[1] Similarly, in humanitarian settings, where maternal and newborn health services are interrupted or altered because of health infrastructure destruction, referral disruption, reduced quality management, and attacks on service providers, women’s and newborn’s access to respectful maternity care is challenged and inequitable.[2] A Report on Accountability for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescent’s health in Humanitarian Settings shows that mistreatment types and RMCabbreviation rights violations in these contexts include: lack of information about accessing MNHabbreviation services, lack of privacy, lack of consent given linguistic and sociocultural diversity, denial or delayed care, neglect and abandonment, and relationships to short-term, foreign aid health workers.

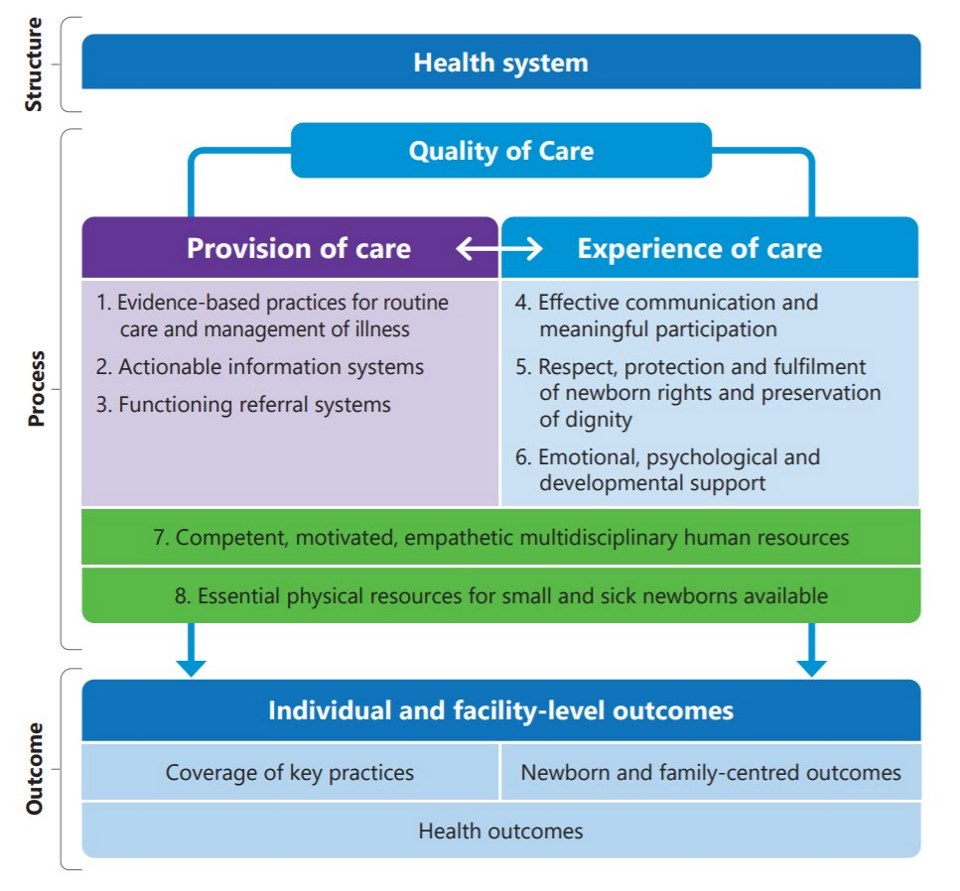

Quality and respectful care are considered a key component of the right to health and the route to equity and dignity for women and children. The domains of experience of care need to ensure that the care provided is family-centred and that newborns, especially small and/or sick newborns, are recognized as active participants and are respected, protected and supported emotionally, psychologically and developmentally (Figure 4.1).

Source: Standards for improving the quality of care for small and sick newborns in health facilities. WHO, 2020.

Accordingly, it is important to implement the following actions to improve quality and enable respectful care are therefore important

- If possible, work with health providers and communities to assess the current status of RMCabbreviation e.g., separation of mother and newborns, ongoing support for bereaved parents and health workers etc, noting gaps and opportunities for improvement.info

- Establish supportive supervision for health providers. Identify a dedicated clinical supervisor who can conduct supportive supervision regularly and can mentor/coach providers on newborn care.

- Use quality checklists on a regular basis to identify areas that need improvement.

- Ensure clinical guidelines and protocols integrate quality improvement and respectful care standards and measures.

- Think through locally relevant culturally relevant newborn practices of IDPsabbreviation and refugees/populations that may be served to promote better experience of care

- Ensure availability and usage of newborn register and data collection sheets; review the data every month and develop an action plan to address issues and gaps identified from the data. Consider involving health care workers, including CHWs and TBAs in the monthly data reviews and action planning to jointly address issues.

- Integrate newborn indicatorsinfo into trainings for M&Eabbreviation officers.

4.3.6 Develop proposals to secure additional funding

Additional funding may be needed to support the activities that form components of the response plan, such as training, material development and procurement of medicines and supplies.

- Because timeframes for developing, submitting and receiving funds can be lengthy, identify funding needs and potential donors as early as possible.

- Utilize experienced grant writers and other staff whenever feasible to prepare and submit proposals.

- Include key program indicators in funding proposals (Section 4.4).