Photo credits: UNICEF/BANA2014-00767/Mawa

“Newborn” and “neonatal” are terms that refer to the first 28 days after birth. Mortality risk during the neonatal period is highest at the time of birth and decreases over the subsequent days and weeks. Up to a third of all neonatal deaths occur within the first 24 hours of birth and close to three quarters occur within the first week of life.[1] This period is also when most maternal deaths occur, rendering labor and birth, and the early postnatal period, a dangerous time for both mothers and their babies. Increasing access to MNHabbreviation services and to lifesaving medical commodities may be the single most important way to improve maternal and newborn survival and health. Around 17% of births globally were not assisted by a skilled health professional in 2020[2] and more than half (52%) of all babies born did not receive a postnatal care visit within two days of birth.[3] It is estimated that improving MNHabbreviation services could prevent up to three out of four newborn deaths, specifically through the increased coverage and quality of preconception, antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal interventions.[4] Newborn care cannot be provided in isolation: the provision of good quality maternal care is just as essential to save lives (Box 2.4). This is why ensuring access to respectful, quality maternal and newborn health services and commodities during humanitarian crisis is critical to improve outcomes for women and their newborns.

Box 2.4: Available Interventions Scaled Up Can Improve Outcomes for Every Newborn and Nations

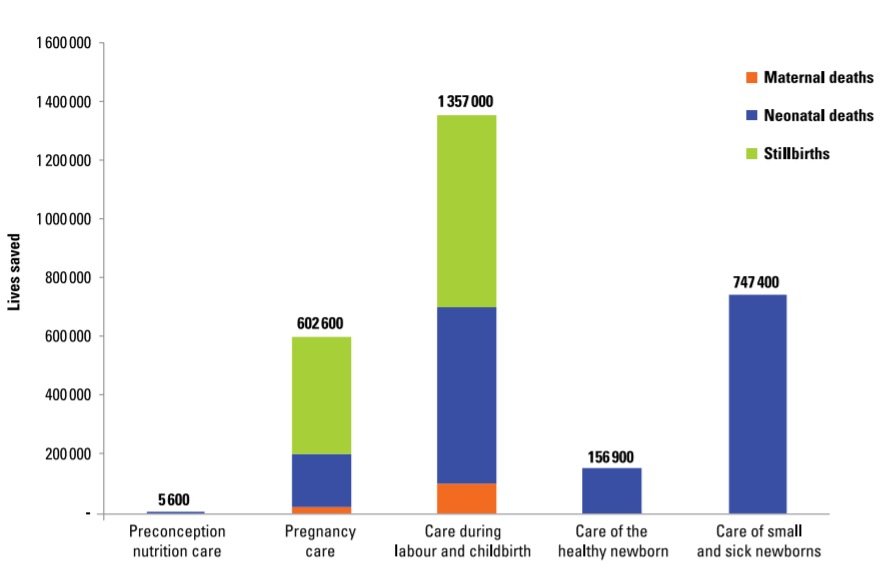

The health of mothers and their babies is so closely linked that the delivery of effective interventions has a triple return on investment with the potential to avert 71% of newborn deaths, 33% of stillbirths, and 54% of maternal deaths at full coverage. These interventions and packages can be scaled up within existing health systems. They are cost effective and will also benefit development outcomes and economic capital.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet 2014, 384(9940):347-70.

2.2.1 Global burden of newborn mortality

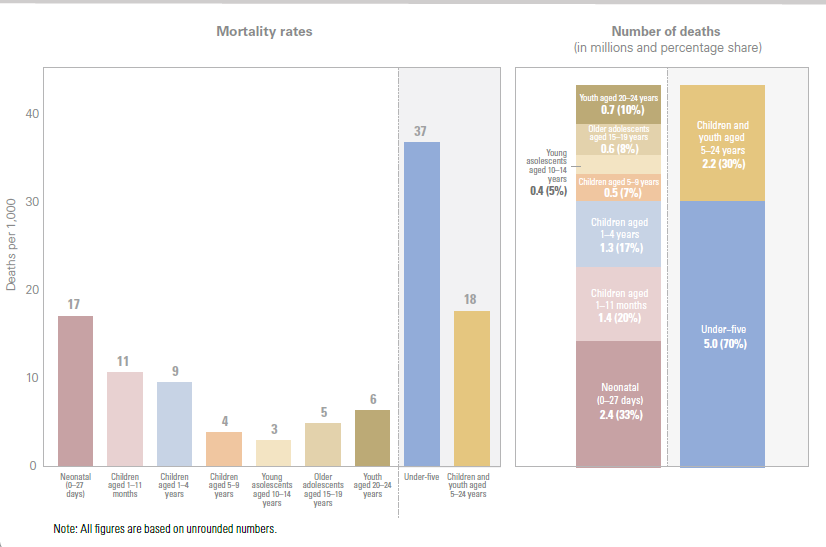

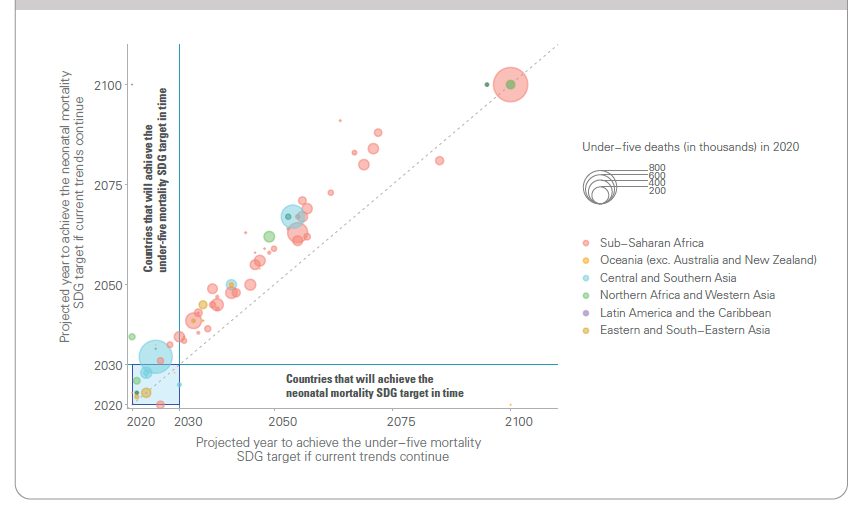

Every year, an estimated 2.4 million babies die within the newborn period,[5] and another 2 million babies are stillborn.[6] Deaths in the first month of life account for half of all deaths amongst children under 5 (Figure 2.1). Yet, up until recently the causes of and solutions to these newborn deaths have received comparatively little attention. Further, crisis-affected countries are shouldering an increasing proportion of the burden of newborn deaths. Figure 2.2 presents a map of global neonatal mortality; 39% of countries at risk of missing the SDG target are classified as fragile and conflict-affected situations by the World Bank. While 122 countries have already achieved the neonatal mortality target, 61 countries will need to accelerate progress to meet the neonatal mortality target by 2030 (see Figure 2.3)–and 53 countries will need to more than double their current rate of decline to meet the target on time. Figure 2.4 lists the top ten countries with the highest newborn deaths in numbers and highest neonatal mortality rates (per 1000 live births) in 2020.

Note: All figures are based on unrounded numbers.

Source: UN Inter-agency Group for Child Morality Estimation. Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2021. UNICEF; WHO; World Bank Group; United Nations. 2021.

Source: UN Inter-agency Group for Child Morality Estimation. Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2021. UNICEF; WHO; World Bank Group; United Nations. 2021.

Source: UN Inter-agency Group for Child Morality Estimation. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2021. UNICEF; WHO; World Bank Group; United Nations. 2021.

Contextualized evidence on the additional burden of deaths in the first month of life in humanitarian contexts is scarce but in all settings the proportion is significant. A comprehensive emergency preparedness and response plan, in any region or nation, should incorporate newborn health services in order to promote a safe and healthy start to life.

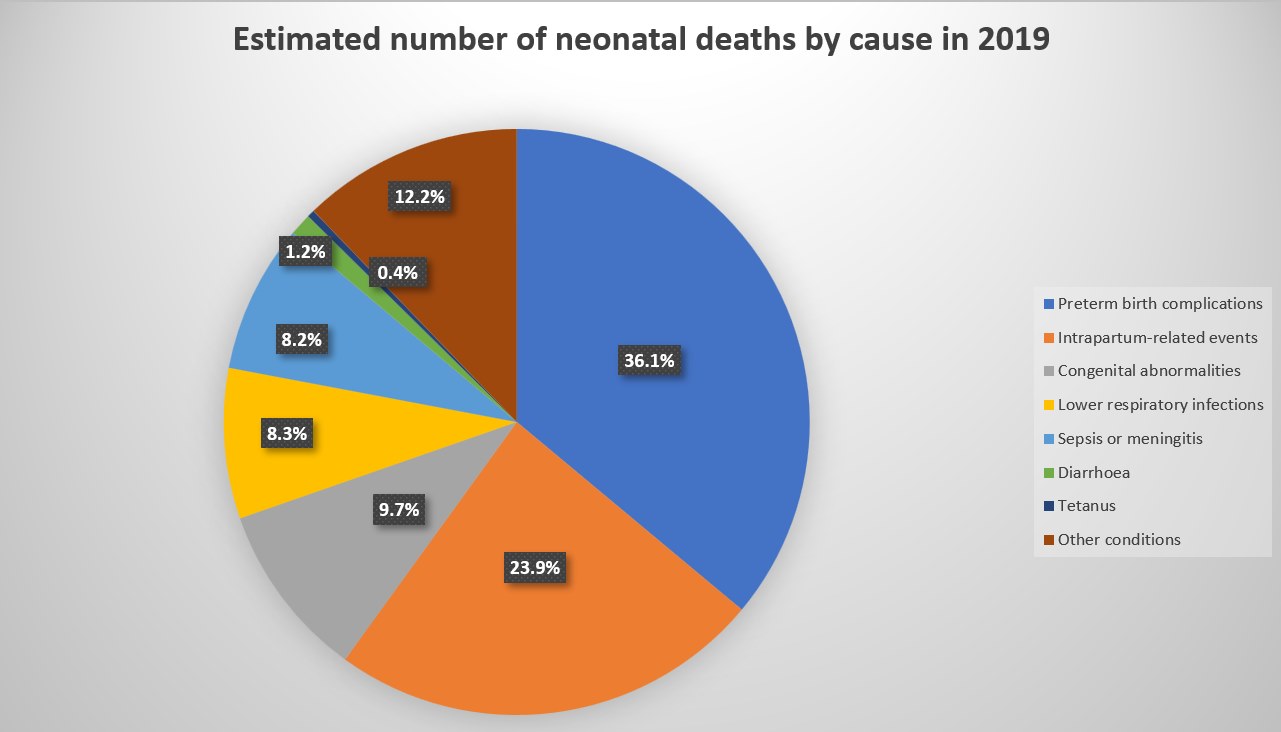

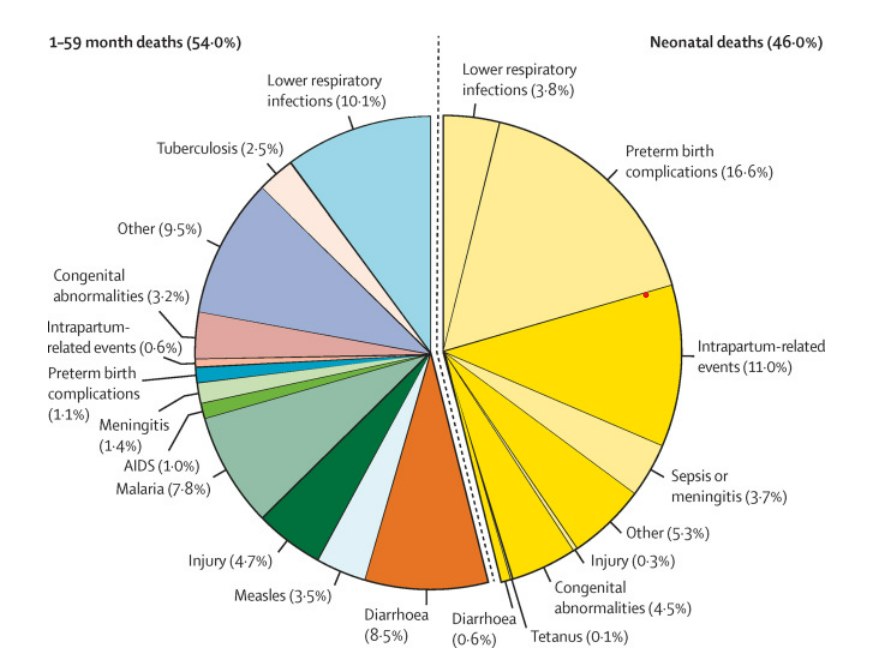

2.2.2 Principal causes of neonatal deaths

Globally, approx. 78% of all newborn deaths result from three preventable and treatable causes: preterm birth complications, intrapartum-related events (including birth asphyxia) and lower respiratory infections (formerly referred to as pneumonia).[7] Figure 2.5 and Figure 2.6 detail the global burden of neonatal mortality by cause.info For stillbirths, over 40% of these deaths occur during labor.[8] Many newborn deaths are preventable with appropriate, good quality care, including in humanitarian settings.

Preterm complications

which refers to babies born before 37 completed weeks of gestation, is among the causes of low birth weight (LBW) among newborns, and renders newborns at higher risk of complications and death.

- Extremely preterm babies are born before 28 weeks of gestation.

- Very preterm babies are born between 28-32 weeks of gestation.

- Moderate to late preterm babies are those born between 32-37 weeks of gestation.

Preterm babies are prone to serious illness or death during the neonatal period. Without appropriate treatment, those who survive are at increased risk of lifelong disability and poor quality of life. Nearly 85% of premature babies are born as moderate to late preterm births.[9] Most small and/or sick newborns, including preterm and low birth weigh babies can be managed with special newborn care that is generally provided at the secondary level hospital. Only one in three small and/or sick newborn requires intensive inpatient care, which can only be provided in a higher-level (e.g. district or tertiary-level) facility.[10] Up to 58% of premature babies could be saved globally through the provision of cost-effective care that can be feasibly delivered in low-resource settings.[11] Most of these interventions can be delivered in humanitarian settings and will save lives (see Section 3.3, Section 3.4, Section 3.5 and Section 3.6.1 for guidance on prevention and care/management of pre-term and/or low birth weight babies).

Intrapartum-related events

includes conditions that occur during labor and birth including birth asphyxia. More than 580,000 newborns are estimated to die annually due to complications during birth based on 2019 estimates.[12] In 2019, as estimated 42% of all stillbirths were intrapartum.[13] The time between a potentially catastrophic event during labor and death can be short, making the first minute a crucial time for babies who may require resuscitation (see Section 3.3, Section 3.4, Section 3.5 and Section 3.6.3 for guidance on managing intrapartum complications at the household level, primary care facilities and in hospitals respectively).

Infections

include neonatal sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis and tetanus. Globally, approximately 410,000 newborns die each year as a result of severe infections, based on 2019 estimates.[14] Most of these deaths could be averted through preventive measures such as vaccination including tetanus toxoid; Improving hygiene during labor and birth and through dry, clean cord care, in line with national guidelines (including the application of 4% CHXabbreviation to the cord in settings where the use of traditional harmful substances on the cord is prevalent- see Box 3.9 for further information); promoting early breastfeeding within one hour of birth; and by ensuring that curative care is available to sick newborns through transfers to health facilities that are equipped to treat infections (see Section 3.3, Section 3.4, Section 3.5 and Section 3.6.2 for guidance on managing infections at the household level, primary care facilities and in hospitals respectively).

Most of the risk factors for the three main causes of neonatal deaths as well as stillbirths are preventable or treatable, including in humanitarian settings (Figure 2.6). However, many causes are unpredictable and rely on preparedness throughout pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period to access timely, respectful, good quality care when needed. By scaling-up a comprehensive set of interventions along a continuum of care shown in Figure 2.7 –from preconception nutritional care, to care of small and/or sick newborns–the annual number of neonatal, stillbirth and maternal deaths could be reduced by an estimated 2.9 million in 81 high-burden countries by 2030. Of these, 1.7 million are estimated to be neonatal deaths and nearly half of the total number of neonatal lives saved would result from providing specific interventions for small and/or sick newborns (i.e. high coverage of quality special and intensive care).[15] In humanitarian settings, comprehensive emergency preparedness, such as ensuring health providers are competent in ENC, including basic neonatal resuscitation and treatment of possible severe infections (see Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5) for more details), is therefore particularly critical because referral may not always be feasible.

Source: Perin J, Mulick A, Yeung D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health. 2021.

Source: Perin J, Mulick A, Yeung D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–19: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health. 2021.

Source: WHO, UNICEF. Survive and thrive: transforming care for every small and/or sick newborn. WHO. 2019.