3.6.1 Prematurity/Low Birth Weight (LBW)

Newborns who are born too soon and/or too small, or who become sick, are at greatest risk of death and disability. Approximately 80% of newborns who die are LBWabbreviation, and two thirds are born prematurely. In addition, a further estimated 1 million small and sick newborns survive with a long-term disability.[1]

Premature Babies

Prematurity refers to babies born before 37 weeks of gestation, and is among the causes of LBWabbreviation among newborns, rendering these newborns at higher risk of complications and death.

| Preterm birth grouping | Gestational age |

|---|---|

| Extremely preterm babies | <28 weeks |

| Very preterm babies | 28–<32 weeks |

| Moderate to late preterm babies | 32–36 weeks |

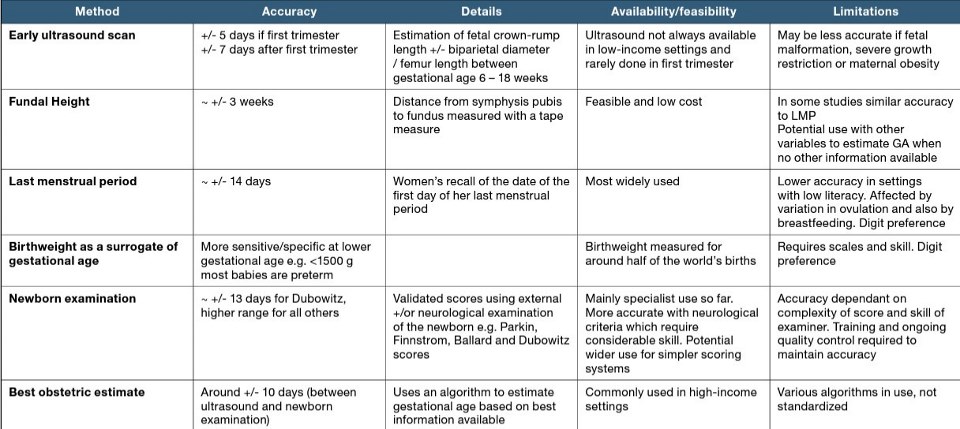

Morbidity and mortality associated with prematurity can be reduced through prevention and care for preterm babies and their mothers. Being born small might be due to prematurity or a baby may be small for gestational age, or a combination of both. LBWabbreviation (less than 2500g/5.5 lb) has been used as a marker for the highest mortality and morbidity risk for babies. However, risk alters with birth size and gestational age, and it’s important to understand the reasons for a baby’s LBWabbreviation as much as is possible in each case. Note that gestational age may be estimated using clinical signs and other proxy measures, but these are often unreliable, particularly in settings with less skilled providers (Figure 3.4). Providers should always ask if a woman has received an early ultrasound.

Source: Adapted from Parker, Lawn and Stanton (unpublished Master’s thesis) in Born Too Soon Report, 2014.

Prevention

There is a lack of highly effective interventions to prevent preterm birth from occurring. The mechanisms causing preterm birth and in-utero growth restriction are not yet well understood and known prevention strategies are often long-term (e.g., multi-generational) and complex. For women at risk of preterm birth, known preventive interventions during pregnancy include identification and treatment of hypertension, close monitoring of multiple pregnancies, and identification and management of underlying conditions like malaria and sexually transmitted infections STIabbreviation such as syphilis and HIVabbreviation.

Once preterm labor has commenced, administering ACSabbreviation to women has been shown to minimize newborn mortality and reduce respiratory distress among pre-term newborns with gestational ages between 24–34 weeks. ACSabbreviation should only be administered once preterm labor has started, at a health facility with the ability to confirm that the gestational age of the fetus is between 24–34 weeks; adequate care is available for preterm newborns and their mothers; and reliable, timely and appropriate treatment for maternal infections is available.[2] ACSabbreviation can be delivered as betamethasone (12 mg intramuscularly, 2 doses 24 hours apart) or dexamethasone (6 mg intramuscularly, 4 doses 12 hours apart). WHOabbreviation has released preterm care guidelines which include more detail on the use of ACSabbreviation.

Other medicines may be included for management of specific complications. For instance, the administration of antibiotics for preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROMabbreviation) has been shown to reduce neonatal morbidity. Tocolytics (also known as anti-contraction medications) can be used to delay preterm births, but there is not yet evidence showing an impact on neonatal mortality. If tocolytics are used to facilitate ACSabbreviation administration or transfer of a laboring mother in emergency situations, nifedipine is the preferred agent, although impact on neonatal mortality has not been established.

Care/management

Thermal care, breastfeeding support, infection prevention and management and, if needed, neonatal resuscitation are the foundational interventions to manage conditions that arise related to prematurity. These interventions can be enhanced with extra care for small and/or sick babies, including:

- Kangaroo mother care, or KMC, in which the baby is carried with skin-to-skin contact (Box 3.2);

- Additional support for breastfeeding, including the use of a breast pump and/or manual expression, administering the milk by cup or another utensil (or by oral/nasogastric tube) and supplementary nursing techniques;

- Treating infections, including with antibiotics as per guidelines; safe oxygen management and monitoring of oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry, supportive care for respiratory distress syndrome and, if appropriate and available, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

For extremely preterm babies with apnea, caffeine administration as per WHOabbreviation guidelines should be considered. In settings where the affected population has access to hospital care, neonatal intensive care provides additional support (Annex 3).[2:1][3] Surfactant is recommended for intubated and ventilated infants with severe respiratory distress syndrome and should only be used in facilities where intubation, mechanical ventilators and associated ventilation equipment and expertise, blood gas analysis and/ or basic laboratory facilities, vital sign monitoring, advanced emergency equipment, and highly specialist newborn nursing, medical and support staff are available.

Low Birth Weight Babies

LBWabbreviation can be a consequence of preterm birth or small size for gestational age, defined as weight for gestation < 10th percentile, or both.[4] Small babies are vulnerable to temperature instability, feeding difficulties, low blood sugar, infections and breathing difficulties. Being born with LBWabbreviation is recognized as a disadvantage for the infant, who will be at higher risk of early growth restriction, infectious disease, developmental delay and death during infancy and childhood.[5]

Improving the care of LBWabbreviation infants through feeding, temperature maintenance, hygienic cord and skin care, and early detection and treatment of complications can substantially reduce infant mortality rates among this vulnerable group.

While basic essential newborn care can be provided in the home and community through trained health workers, small and/or sick newborns, including preterm and LBWabbreviation babies will usually require inpatient care. Most small and/or sick newborns, can be managed with special inpatient care that is generally provided at the secondary level hospital. Only one in three small and sick newborns requires intensive inpatient care, which is provided in tertiary level hospitals.[6]

Whenever possible, small and/or sick babies should be transferred to a hospital for care in a dedicated ward or space, staffed by health workers with specialist training and skills that can provide thermal support (KMCabbreviation wherever possible), feeding support, infection prevention and treatment, jaundice treatment and growth monitoring. After the newborn is stable, support outside the health facility has been established, and mothers and caregivers have learned and initiated KMCabbreviation, many small babies can be discharged to continue KMCabbreviation and monitoring at home.

In humanitarian settings where access may be limited, activities such as KMCabbreviation, breastfeeding, CHXabbreviation for cord care (context specific), strict hygienic practices with hand washing for caretakers and health workers, and if infection is suspected, antibiotic treatment should be prioritized.

3.6.2 Newborn Infections

Preventive measures during the antenatal period and labor/delivery protect the health of the mother and reduce the risk of congenital and newborn infections. Clean birth practices, including hand washing before, during and after birth, are critical (Figure 3.2). Timely management and treatment of birth complications are important factors in reducing newborn and maternal mortality. To give women access to life-saving care, standard guidelines recommend that all births take place in a health facility under the care of a skilled provider. Yet, because of the logistical challenges and resource limitations of crisis settings, many women might give birth at home and require household-level care. CHWs and other field workers should be tasked with conducting community outreach and postnatal follow-up at the household level to identify and transfer newborns with infections to health facilities equipped to treat them.

See Box 3.3 for a list of clinical signs and symptoms of newborn infections that can be used by CHWs and family members, and Box 3.4 for signs and symptoms that can be identified by trained healthcare workers. It is important to ensure that primary care facilities as well as hospitals are sufficiently equipped to manage newborn infections, including equipment, medicines and referral plans for household to health facility transfers. Health staff should be trained to manage newborns with possible serious bacterial infections. See Annex 1C for a summary table of services to prevent and manage newborn infections and sepsis, presented by level of care.

At the primary care facility and hospital levels, staff must be especially vigilant in investigating clinical indications of infections in newborns, giving special attention to:

- Malaria: In a malaria-endemic area, testing for malaria should be undertaken prior to performing a lumbar puncture. A malaria smear can be used as a rapid diagnostic test as the HRP-2 protein may be transmitted from a malaria-infected mother to her baby during pregnancy.

- Sepsis, meningitis, and pneumonia: The most common infections in the newborn are sepsis, meningitis and pneumonia. Signs of these infections, which may be bacterial, require treatment with antibiotics. These infections present as critical illness, clinically severe infection or isolated rapid breathing.

Box 3.4 includes guidance on clinical signs for infections in newborns.

3.6.3 Intrapartum Complications

Intrapartum complications occur during the time of labor and delivery and cannot always be predicted, though much can be done to prevent them, including in humanitarian settings. Ensuring quality and respectful antenatal care and skilled care at birth with timely action when needed are much more effective in preventing intrapartum complications than known strategies for management. All delivery areas should be prepared to provide management of intrapartum complications, such as breathing support. Supplies should be prepared and available before a birth occurs so that safe and timely treatment can be given if the baby is born not breathing or in distress. If this is not possible, any woman who has prolonged labor should be referred as there is a higher risk for fetal distress. Follow the steps outlined in Section 3.3.3, Section 3.4.2 and Section 3.5.3 to manage intrapartum complications at each level of care. For more guidance on intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience, refer to [WHOabbreviation’s 2018 guidelines](https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550215).