Photo credits: UNICEF/MLWB2011-00287/Noorani

ENCabbreviation is the basic care required for every baby that should always be prioritized in a humanitarian setting, irrespective of where they are born (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1: ENC Components: Services for All Newborns

- Thermal care: Drying, warming, skin-to-skin contact, delayed bathing

- Infection prevention/hygiene: Clean birth practices, hand washing, clean dry umbilical cord care, and clean eye/skin care. Application of CHX for cord care (7.1% chlorhexidine digluconate aqueous solution or gel, delivering 4% CHX) in the first week after birth is recommended only in settings where harmful traditional substances (e.g., animal dung, dust, clay, mud) are commonly used on the umbilical cord (Box 3.9)

- Initiation of breathing: Thorough drying, clearing the airway only if needed, stimulation through rubbing the back, basic neonatal resuscitation using a self-inflating bag and mask for babies who do not spontaneously breathe

- Feeding support: Skin-to-skin contact, support for initiation of exclusive breastfeeding within one hour of birth, not discarding colostrum (or first milk)

- Monitoring: Frequent assessment for danger signs of serious infections and other conditions (Box 3.3 and Box 3.4) that require extra care outside the household or health post

- Postnatal care checks: All women and babies should receive a minimum of three postnatal checks during the first month after birth and an additional postnatal contact during week 6. This includes postnatal care for healthy women and newborns in the facility for at least 24 hours where feasible. If the birth took place at home, a postnatal check as soon as possible within the first 24 hours (which are the most critical), between 48 and 72 hours, between days 7–14, and during week 6 after birth.info

- Delayed cord clamping immediately after birth (where feasible), vitamin K and tetracycline eye ointment within the first 24 hours should be provided as part of essential care for all newborns.

- Provision of vaccinations as per the national immunization schedule

For at least the first hour following birth, the newborn should be placed skin to skin with her/his mother to ensure warmth, encourage early feeding and promote bonding. If KMCabbreviation is implemented within the response or catchment area, mothers and family members should be counselled and supported accordingly (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2: KMC: Helping Small Babies Survive and Thrive

KMCabbreviation is one of the most important interventions to save preterm and LBWabbreviationbabies in all settings. This form of care, initiated in health facilities, involves teaching health workers and caregivers how to keep newborns warm through continuous, 24 hours per day, skin-to-skin contact on the mother or caregiver’s chest. While current WHOabbreviation recommendations indicate starting KMCabbreviation only after the baby is stabilized, recent evidence indicates that compared with the existing practice, starting KMCabbreviation immediately after birth can save up to 150,000 more lives each year.[1]

In settings where home-based deliveries are still occurring or access to a health facility is limited, community initiated KMCabbreviation could improve survival. Even for settings with high rates of institutional birth, KMCabbreviation initiation at health facilities may not happen and even if it does, it is possible that hospital to community continuum of care is not strengthened. In such situations, community KMCabbreviation programs could be cost effective if the health workers are trained in KMCabbreviation and could promote it during their routine home follow up visits.[2] Implementation research is still needed to adapt these findings to humanitarian settings.

Getting started with KMCabbreviation:

- Not much is needed to start KMCabbreviation other than designated beds with infection and access control and access to extra care if complications arise

- Health workers should counsel mothers and families with small babies to initiate KMCabbreviation as soon as possible after birth, particularly in the absence of intensive neonatal care

- If the mother is not available, fathers and other family members can also provide KMCabbreviation

- The environment where KMCabbreviation is practiced should be kept warm, above 25°C if possible

Positioning:

- Dress baby in only socks, nappy, and hat

- Place baby between mother’s breasts, in vertical position, with head turned to side, slightly extended to protect airway

- Flex hips in frog position

- Flex arms

- Wrap/tie baby securely with cloth to mother

Feeding:

- Mother provides exclusive breastfeeding 2 to 3 hourly, and on-demand

- If baby unable to latch/suckle, feed expressed breastmilk with cup or spoon

Duration:

- LBWabbreviation and premature babies should remain in KMCabbreviation for at least 20 hrs/day (with mother or surrogate) until baby no longer tolerates KMCabbreviation positioning

- Mother should sleep in a half-sitting position, with baby tied in KMCabbreviation

- If baby needs to be out of KMCabbreviation position, care should be taken to keep baby warm

Follow-up:

- Mother and baby should be sent home in KMCabbreviation position with counseling prior to discharge and follow-up monitoring as clinically indicated

For further guidance on providing KMCabbreviation, please refer to WHO’s Kangaroo Mother Care: A Practical Guide.

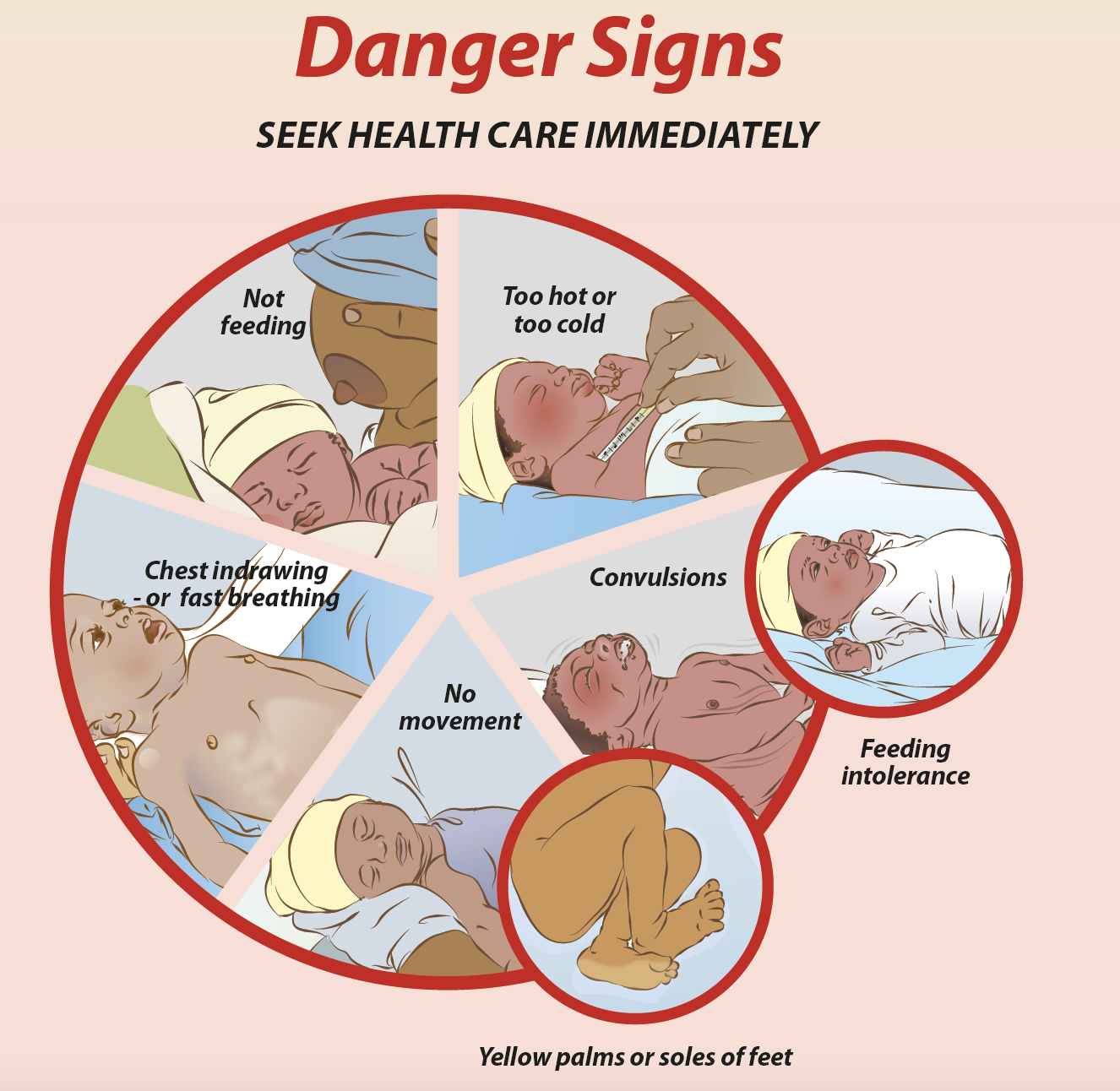

Following this, and throughout the neonatal period at every visit, newborns should be examined for indications of life-threatening conditions. Danger signs for severe illness in newborns, which all families, CHWs and service providers should be aware of, are listed in Box 3.3. Box 3.4 lists the signs of newborn infection that can be recognized by formally trained medical personnel. The condition of a newborn, especially those who are small, can deteriorate quickly. Families and CHWs should have a plan for seeking extra care that accounts for possible changes in the logistical and security situation in the local area. It is critical that the mother and baby are not separated, particularly immediately after birth and including during referral, unless medically necessary. This simple action can save lives, particularly in humanitarian settings where newborns may be more exposed to hypothermia, infections and delayed breastfeeding.

The sections below provide guidance on newborn and maternal health care measures to prioritise leading upto and after birth at each level of care to enhance newborn health outcomes. These recommendations ideally need to be situated within the broader SRMNCAHabbreviation continuum of care and supplemented by comprehensive maternal-newborn health care interventions as dictated by the MISPabbreviation and the Inter-agency Field Manual on Reproductive Health in Emergencies.

Box 3.3: Danger Signs of Serious Illnesses in Newborns

If any of the signs listed below are noticed, CHWs and family members should immediately refer a newborn to a health facility for further care.

- Not feeding well

- Fits or convulsions

- No movement or reduced activity

- Fast breathing (more than 60 breaths per minute)

- Severe chest indrawing

- Feels too hot or too cold to the touch (temperature above 37.5°C/99.5°F or below 35.5°C/99.5°F)

- Yellow skin, eyes, palms or soles

Note: See Box 3.4 for danger signs of newborn infection that can be used by formally trained medical personnel.

Infographic source: Essential Care for Small Babies Parent Guide (Africa)

Citation: WHO Recommendations on Newborn Health. Guidelines Approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee, 2017

Box 3.4: Signs of Serious Bacterial Infection in Neonates

Sepsis, meningitis and pneumonia in neonates can be difficult to detect in crisis settings, where diagnosis is typically clinical. If laboratory diagnosis and x-ray are available, blood culture, blood count and differential, and lumbar puncture may help in the diagnosis of sepsis and meningitis. X-ray may help in the diagnosis of pneumonia. However, in most settings, diagnosis is based on clinical signs that can be used to differentiate critical illness (e.g., meningitis), clinically severe infections or complications of infections (e.g., sepsis) and isolated rapid breathing (e.g., pneumonia).

The following danger signs can be used by formally trained medical staff to start treatment of neonatal infection. See Box 3.3 for danger signs for use by CHWs and family members.

Critical illness: no movement/unconscious, history of convulsions, unable to feed, severe bleeding, or bulging fontanelle, weight <2kg

Clinically severe infection: Fever (temperature greater than or equal to 38°C), hypothermia (temperature less than 35.5°C), not feeding at all or not feeding well on observation, reduced movement, severe chest in-drawing

Isolated fast breathing: Respiratory rate >60 breaths per minute

For more information, see Management of the sick young infant aged up to 2 months, WHO and UNICEF, 2019 and Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A guide for essential practice (3rd edition), WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF, 2015.